Why drug resistance should be on our radar

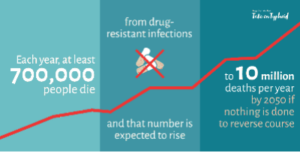

Drug resistance occurs when bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites change over time and no longer respond to treatment. As a result, medicines become increasingly ineffective, and infections are more difficult to treat. The need for preventative action to avert increasing drug resistance is crucial. Drug-resistant infections lead to more difficult diagnosis, longer hospital stays, higher medical costs, and increased mortality.

How we got here

Drug resistance doesn’t occur overnight—it gradually develops as pathogens evolve. Increased movement of populations means increased movement of disease. As populations become more mobile, the risk of importing drug-resistant diseases increases. Extreme climate events, poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure, migration, and inadequate infection prevention can facilitate the spread of drug resistant pathogens, especially in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Countries such as Pakistan, DRC, and Bangladesh experience the double burden of drug resistance and climate change, which can lead to a host of negative health outcomes, including increased morbidity and mortality.

Prevention is possible

Drug resistance is a serious threat to human lives. Prevention with vaccines is an effective way to protect against drug resistance.

Multidrug-resistant (MDR) and extensively drug-resistant (XDR) strains of Salmonella Typhi, the bacteria that cause typhoid, have been increasing in many regions. Countries with a high burden of typhoid often experience inappropriate use or overuse of antibiotics. Typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCVs) are available and can stop typhoid in its tracks, thereby reducing the need for antibiotic treatment by preventing people from getting sick in the first place. The combination of improved WASH infrastructure, together with increased access to TCVs, work to combat drug resistance from the very start. Evidence suggests that increased immunization coverage has the potential to reduce the overuse of antibiotics. Decreased rates of illness lead to reduced transmission and therefore, less need for antibiotics and less strain on the health care system and local communities.

Increased awareness

The World Health Organization (WHO) has developed a Global Action Plan to tackle the issue. Part of this plan includes World Antimicrobial Awareness Week (WAAW), an annual campaign to increase awareness of drug resistance. This year, we celebrate with the theme of “Preventing Antimicrobial Resistance Together.” It is critical for policymakers, health workers, and stakeholders to work collaboratively to address drug resistance across diseases and geographies. Global forums, such as a recent typhoid regional meeting in Dhaka, represent opportunities for meaningful collaboration and action. Additional opportunities to raise awareness have come in the form of WHO consultation meetings with stakeholders from around the globe.

Taking on typhoid together

No one can fight drug resistance alone. Pathogens don’t know borders; we need to work together to ensure everyone is protected and no one is left behind. Actions to reduce the overuse of antibiotics and conversations about investments in vaccines such as TCVs must be a central focus. Drug-resistant strains of typhoid will continue to spread unless TCVs are prioritized in countries that need them most. Regions must think cooperatively, counties must work together, and policymakers must collaborate to confront drug resistance head on.

Cover photo: Children wait to receive TCV in Pakistan. Pakistan has high rates of drug resistance, and TCVs are a great tool to protect kids from drug-resistant typhoid. Photo: PHC Global