On a recent visit to Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital and largest city, I saw how much suffering occurs due to typhoid. From Dhaka Shishu Hospital – the country’s largest children’s hospital – to local health outposts, I watched mothers carry their feverish children to be tested for typhoid. This is not an unusual sight. Most people in Bangladesh have had a family member, colleague or friend infected with the disease, contracted through consuming contaminated food or water.

Based in a setting with one of the highest typhoid burdens in the world, the International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh – better known globally as icddr,b – began focusing their research on typhoid more than a decade ago. An important step in fighting the disease? Improving diagnostic and prevention efforts. Typhoid is often misdiagnosed, with symptoms easily mistaken for those of malaria or dengue. A confirmed typhoid diagnosis requires a blood or bone marrow culture, which is not often available in local community health centers.

“We saw the limitations of the existing methods of typhoid diagnosis,” said Dr. Firdausi Qadri, who is leading the Infectious Disease Division of icddr,b. “There is a need for a diagnostic test that is rapid but also sensitive and specific, can be used in low-resource settings, and is not influenced by a patient’s prior usage of antibiotics.”

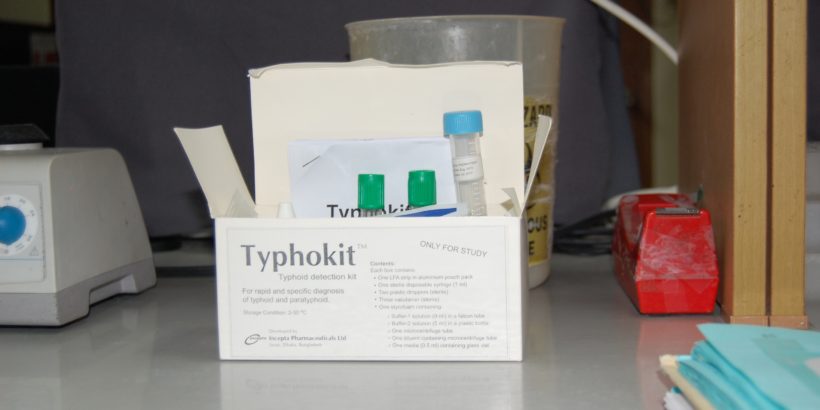

At their lab in Dhaka, icddr,b’s team of researchers are developing sensitive and fast diagnostic methods to overcome these challenges. One of their diagnostic kits, Typhokit, is currently undergoing testing and could be an important tool for determining not only the burden of disease, but the effectiveness of prevention and control methods.

Icddr,b’s work extends beyond diagnostics. In 2016, the Center began a typhoid surveillance project in partnership with Professor Andrew Pollard and his team at Oxford University to track typhoid cases in Mirpur, a low-income area of Dhaka that is a hub for typhoid patients. Despite a population of more than 4.5 million people, most of the people in Mirpur have come into contact with iccdr,b one way or another as the organization has grown its presence in this area with different health projects. For example, a one-room clinical site has expanded into a multi-story field clinic and office with community health centers for studying enteric fever, diarrheal diseases, and vaccines.

“We have followed many of the children in this area since their birth,” said Dr. Farhana Khanam, a researcher at icddr,b. This project deploys health workers to visit each household multiple times a year, tracking health patterns and offering primary care services. These data and strong relationships with the community will be invaluable when icddr,b, as part of the Typhoid Vaccine Acceleration Consortium (TyVAC), vaccinates more than 40,000 children in Mirpur in the coming months with the newly prequalified typhoid conjugate vaccine, Typbar TCV®, to evaluate the impact of the vaccine in real-world settings.

On my visit, I accompanied icddr,b’s researchers and health workers to the neighborhoods they will focus on in the upcoming vaccination campaign. I watched them ask people questions ranging from how many people live under one roof to whether any of those family members had recently had a fever. The health workers enter responses into a tablet that uploads the information to a main server at their office. There, researchers can see the patterns of a disease like typhoid take shape over a colorful digital map of the area.

This map will soon include data on the vaccine campaign in Mirpur. The data will be used for vaccine effectiveness studies, a part of the greater TyVAC goal of providing decision-makers with data on the impact of typhoid conjugate vaccines in communities at risk of typhoid. With this data, and over a decade of experience working to prevent typhoid, icddr,b will help Bangladesh make informed decisions on the best strategies for typhoid prevention and control. And by taking on typhoid, hospitals in Dhaka and around the country will see fewer mothers coming through their doors with feverish children seeking care.

Photo Credit: Sarah Lindsay