The introduction of typhoid conjugate vaccines (TCV) into a national immunization system takes sizeable resources. Teams from various government offices, agencies, and civil society organizations must work together to plan a campaign. Importantly, this planning includes organizing social mobilization activities to motivate individuals and communities to access TCV and participate in the campaign. Activities are specific to the local context, nuanced to provide information and clarity for a specific community or region.

In Pakistan, social mobilization led by PHC Global has played a crucial role in reaching nearly 30 million children with TCV. We’re publishing this three-part series about the use of the arts in social mobilization for TCV to highlight how one unique approach interwove art, creativity, and health, to reach local community members in Pakistan.

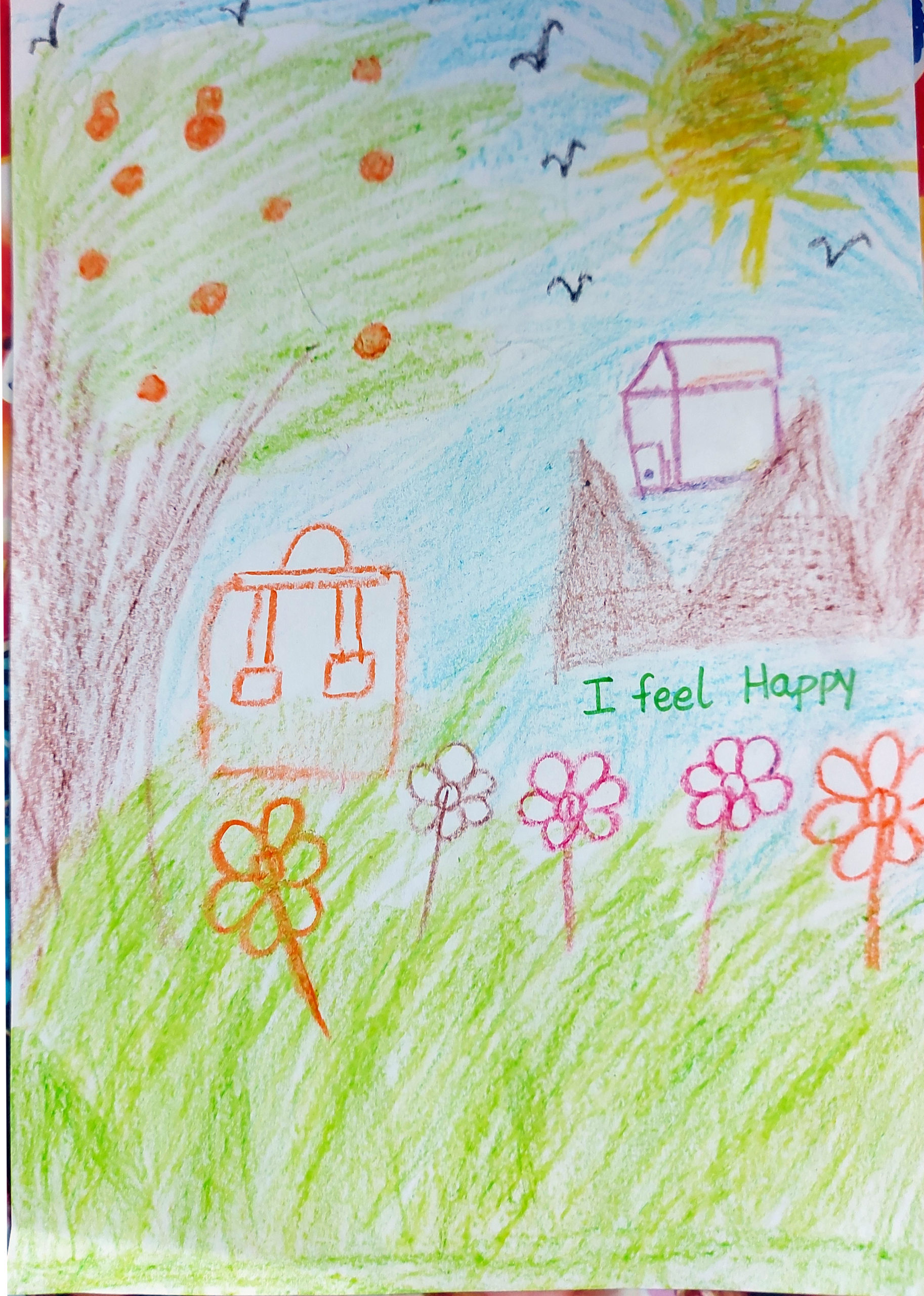

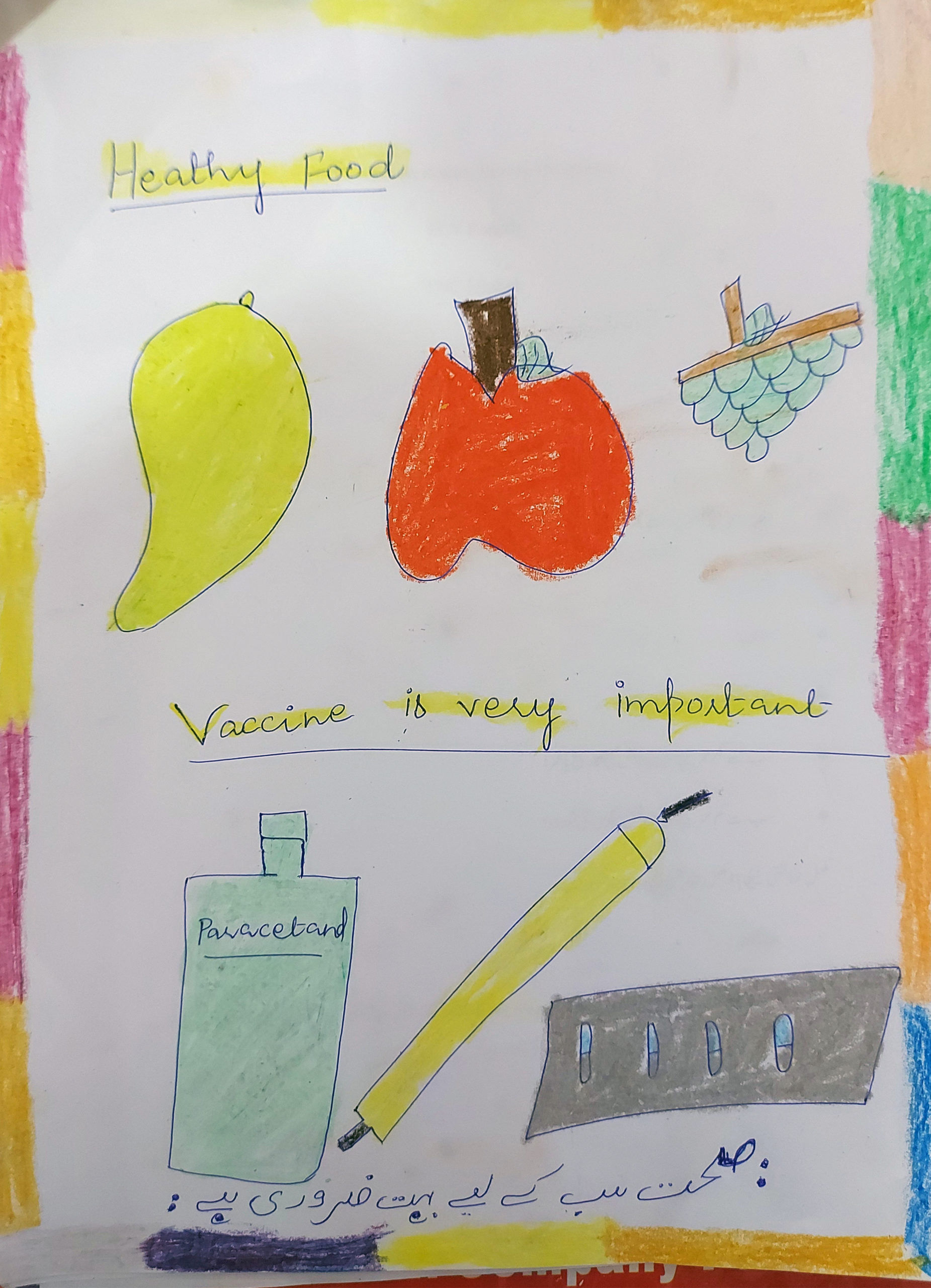

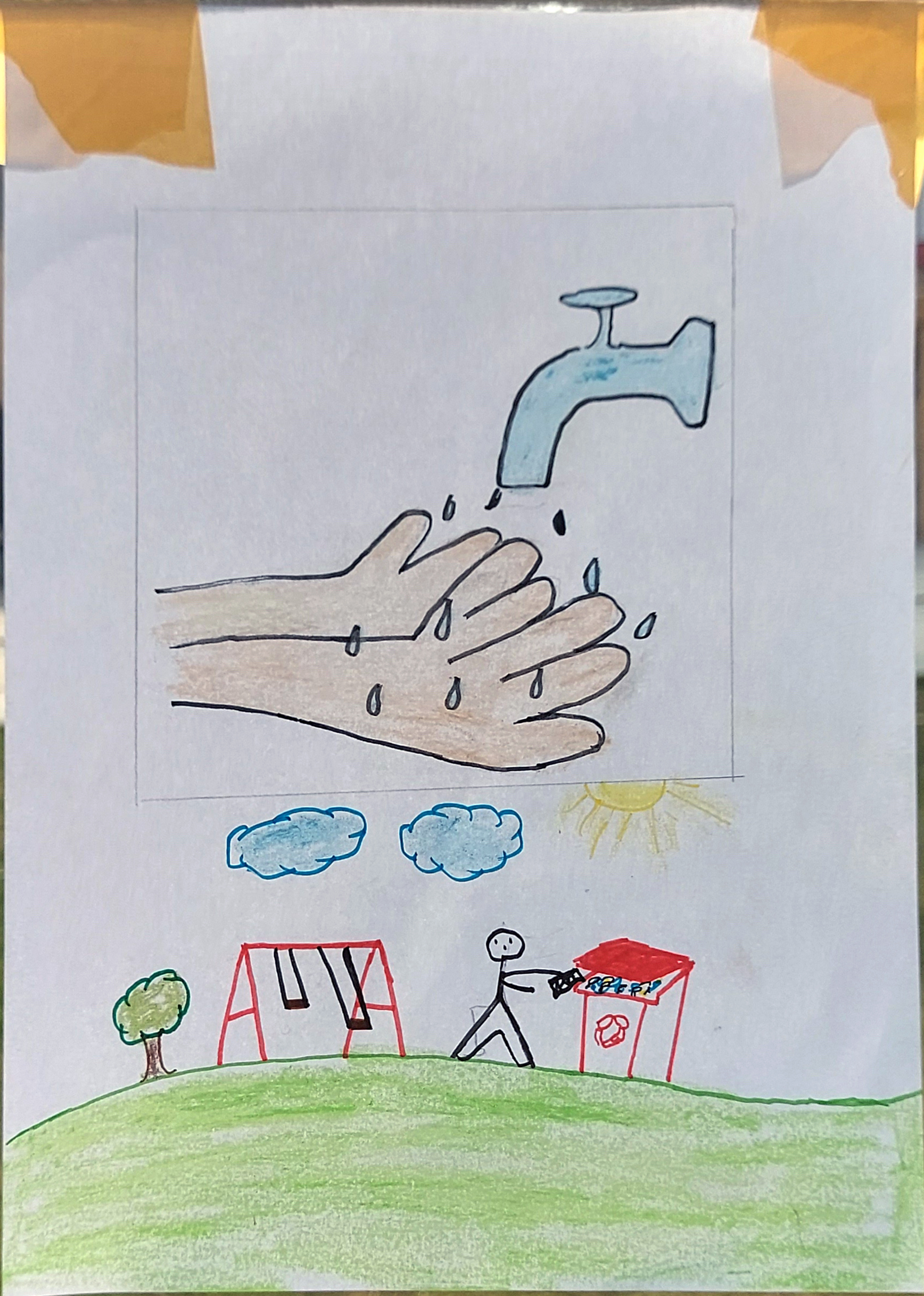

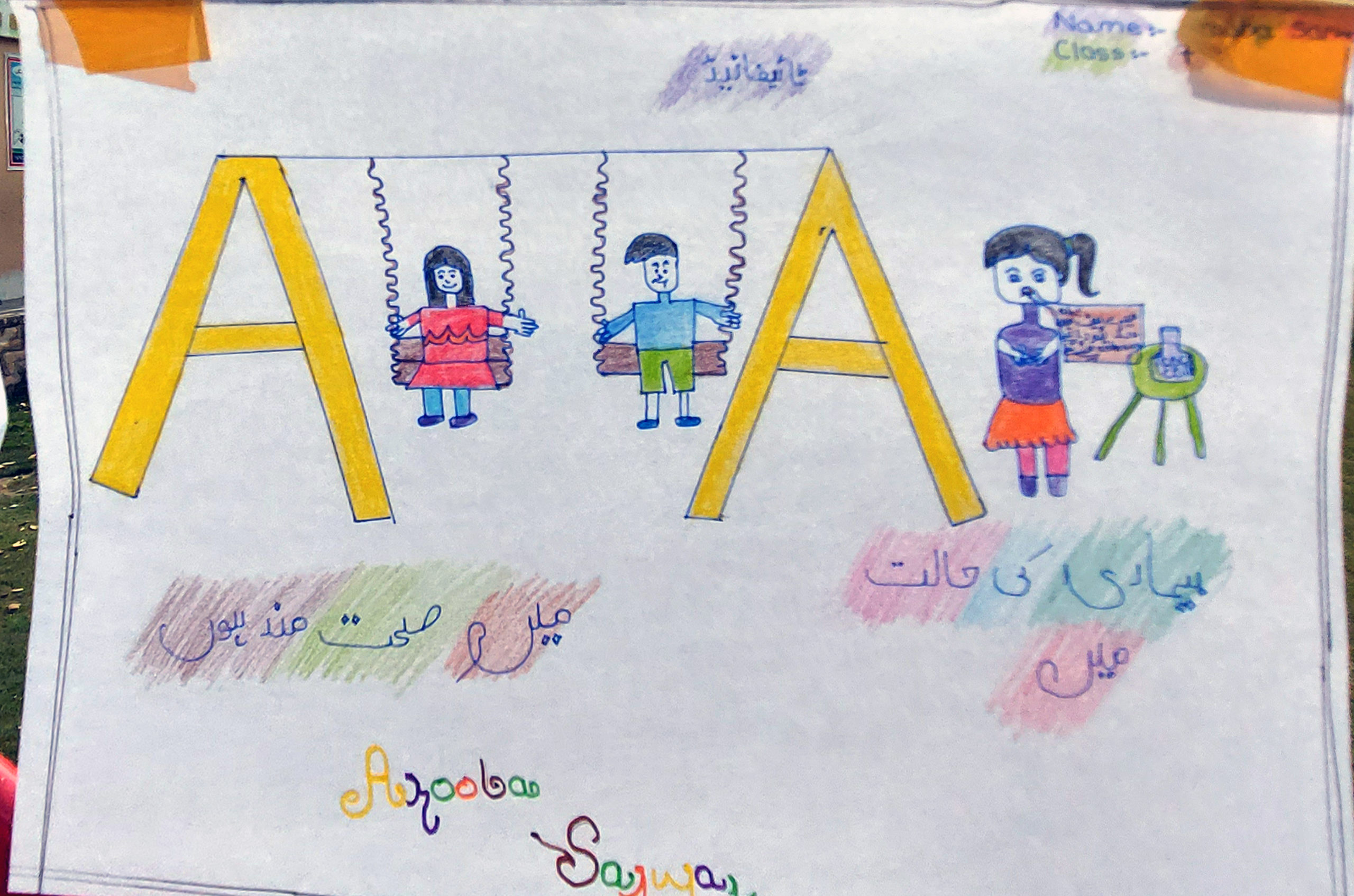

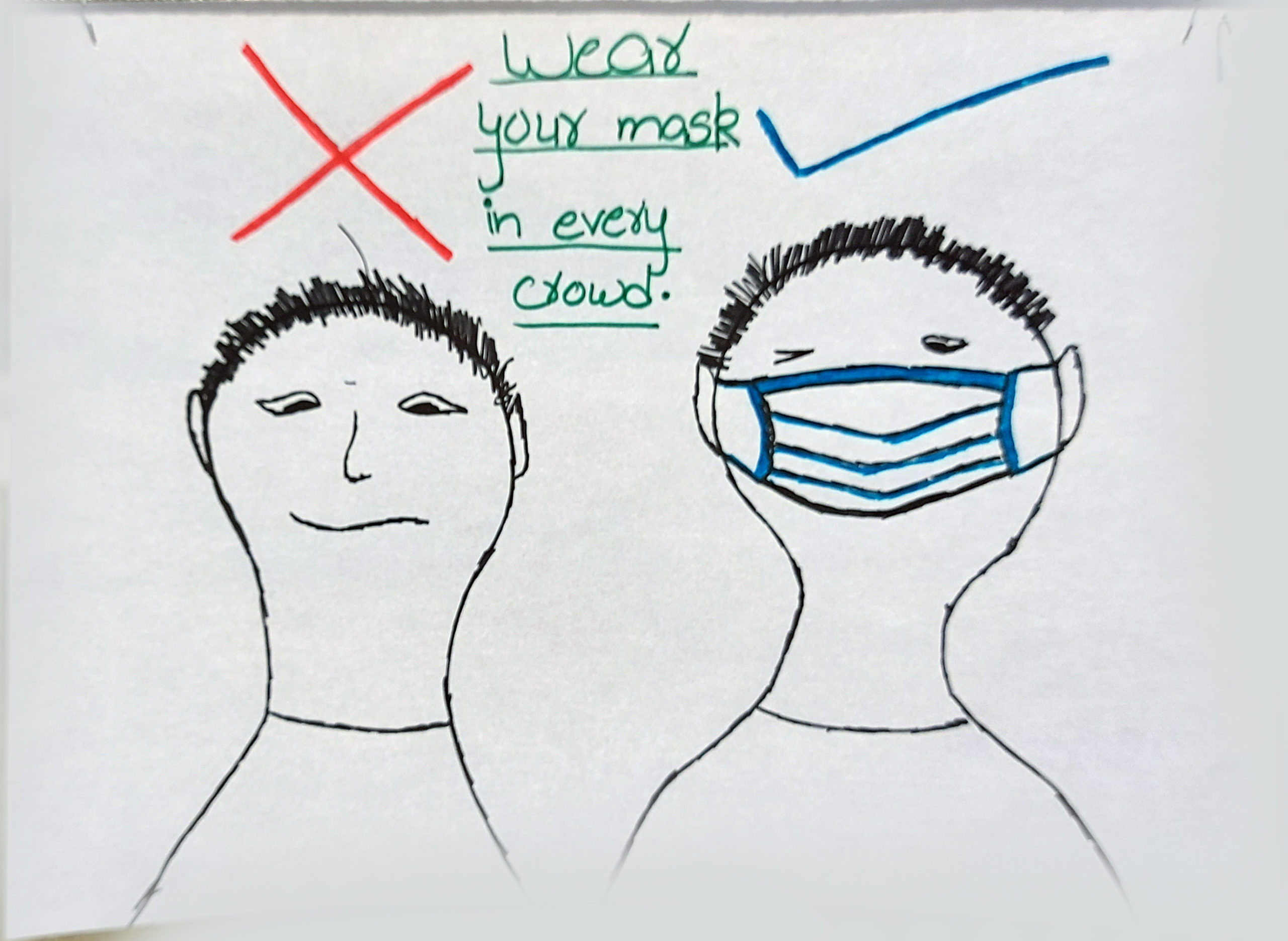

View examples of the arts created through this mobilization in the slider below:

During the social mobilization sessions, the PHC Global team took field notes reflecting on the experience as well as photographic and video documentation. They also gave attendees at each session pre-and post-tests. Community groups took a short vaccine hesitancy questionnaire developed by the WHO SAGE Working Group. Health workers took the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. While the scope of these small surveys cannot generalise findings, the results do qualitatively point towards the effect of our approach and provide insight into how to evolve and improve the sessions.

Establishing a foundation of knowledge about typhoid

We rooted each session based on a number of assumptions. With the communities, we assumed that:

- People care for their health and the health of their families and communities.

- By creating agency, communities are more likely to act with responsibility and make informed decisions.

- By establishing a dialogue in a “safe environment,” people speak of their fears and expectations. These may have direct and indirect implications on effective communication strategies.

Therefore, as a first step in facilitating community agency, we acknowledged that the community had some awareness of typhoid and was not being dictated to take action. Therefore, our sessions started based on the knowledge they already possessed around typhoid. Once rapport was established, the health staff offered clarifications, corrections, or technical details. This was the foundation for the action that the communities would take to get their children vaccinated and encourage others in the community to do the same.

“It is called ‘The Big Fever’ in our language and patients have a very high fever that goes on for a long time along with belly ache and diarrhoea and weakness… it comes from gandagi (dirt) and dirty food… ” ~ 70 plus year old grandmother of 12, Faisalabad

“Of-course I will get my children vaccinated and I will tell my extended family to do so also.” ~ Female participant, Khanewal

Community members also openly talked about cultural and religious reasons that support preventive measures such as immunisation.

“There is an Islamic imperative to prevent disease before it occurs…” ~ Religious leader, community session, Multan District, who continued by reciting an excerpt from the Quran and a Hadith (saying of the Prophet)

Addressing community questions and vaccine hesitancy

After some basic information about the TCV campaign and the importance of getting children vaccinated, participants were encouraged to ask questions. The most common concerns raised had to do with side effects, vaccine quality, and the confusion related to several vaccination programmes happening simultaneously (e.g., polio, TCV, and COVID-19 campaigns). Participants also realised that vaccination was just one part of the solution:

“ …if we vaccinated our children, will the disease not come back in the house because the streets are so filthy and the flies will carry the disease inside again?” ~ Young participant, Community session, Vehari

Such discussion raised the issue of multi-sectorial approaches, public and personal responsibility, and public education. And the bottom line was personal agency:

“We can’t wait for the government to do this or that… in the end it is up to me how I take care of myself and how I behave.” ~ Participant Community session, Vehari

As we conducted the sessions and measured changes in perceptions, we were acutely aware of the possibility of a response bias, whereby interviewees may answer questions based on what they think is expected, rather than how they truly feel. As anticipated, the respondents were more inclined to agree with positive statements in the pre-test vaccine hesitancy survey. However, after the session, there were some shifts in the responses (in both directions) that point towards a process of critical thinking. As an example:

New vaccines carry more risks than older ones.

In pre-session most responses were agree and completely agree. In the post-test, responses turned into disagree/strongly disagree, which is a positive change.

I am concerned about serious adverse effects of vaccines.

On this item, pre-session responses were mostly somewhat agree. This shifted to strongly agree in the post-test.

Although it may seem intuitive to be discouraged by this increased expression of disagreement or doubt, this shift in the response measures the person’s agency, and the trust of a safe space, to answer openly with an honest opinion. When people are provided the opportunity to critically look at an issue with all relevant information in a safe space, they will use their agency to raise doubts and decide on the best options for themselves. It also points towards the creation of trust when someone feels safe enough to raise a doubt and ask a question.

Importantly, when a participant raises a doubt or question, he/she must be provided with accurate information. By providing answers to a person’s questions, it is more likely to lead to behaviour change, as compared to situations when people are simply directed to follow certain protocols and comply outright. Most importantly, we must view doubts and concerns as “real” questions being raised by the communities. We must then consider these concerns when developing a strategic communication strategy.

Improving mental health and motivation of health care workers

During the sessions with health workers, we assumed that:

- The health teams were experienced and working to their full potentials.

- The working environment during a vaccination campaign can be extremely stressful.

- Recognising, validating, and encouraging health teams will lead to enhanced motivation and better outcomes.

During the health worker sessions, we held initial discussions and then turned the focus to art-making activities. We designed these activities to enhance self-esteem through personal resource identification as well as team building. Furthermore, with respect to the high-stress environment of the vaccination campaigns, we practised and taught stress-relieving activities (e.g., breathing exercises).

“This session was incredible. I have not felt so relaxed in such a long time. We need more of these sessions.” ~ Health Manager, Islamabad

“I realize how important my work is and how much I enjoy helping others even when it is such a stressful and thankless job.” ~ Health Manager, Multan District

“Even if am not acknowledged for my hard work, I know in my heart how important I am for the campaign.” ~ Health Manager, Kot Addu

In every session, there is a skeptic or two who challenges the premise and is not convinced about using art for health or social mobilization. However, the group tends to respond to the skepticism organically:

“Why are we writing poems and making drawings, what does all this have to do with the TCV campaign?” ~ Health Officer, Shiekhupra

The response from a fellow colleague:

“You and I – the people – that is the connection! How can we work well if we are so tired and stressed and hate our jobs?”