By today’s standards, enteric fever, which includes typhoid and paratyphoid, is easily treatable and preventable – but in the days before antibiotics and vaccines, outbreaks of these diseases were so devastating that they could endanger entire civilizations. Researchers have known since 2006 that typhoid fever may have been responsible for the great “plague of Athens” in the 5th century B.C., which killed 100,000 people – a third of the city’s population – and led to the eventual dissolution of their empire. But enteric fevers’ ruinous impact did not stop there. As it turns out, enteric fevers may be responsible for the downfall of not one, but two great civilizations.

A study recently published in Nature found that ancient bacteria recovered from the teeth of bodies buried in southern Mexico revealed that a strain of Salmonella – likely to be Paratyphoid C – may have brought about the catastrophic downfall of the Aztec civilization. If true, the Aztecs may join the ancient Athenians in the ranks of entire societies brought down by this disease family.

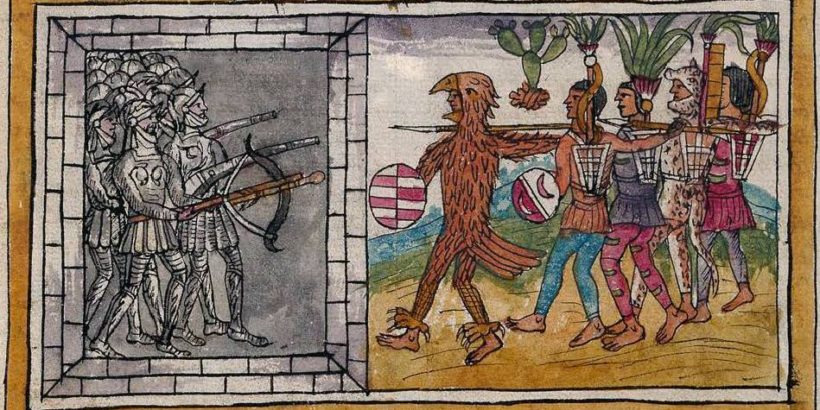

Following the Spanish invasion of Mexico in the 16th century, multiple deadly epidemics called cocoliztli, or pestilence, devastated the Aztecs. These cocoliztli may have wiped out up to 80 percent of the population, as many as 18 million people. Contemporary accounts describe so many corpses that “from morning to sunset the priests did nothing else but carry the dead bodies and throw them into the ditches.” Until now, the exact identity of this mass killer has been a mystery. The revelation that paratyphoid has been raised as the possible main culprit sheds light on the dangers of all enteric fevers.

The bacteria that causes the most common enteric fever, typhoid fever, may be as old as human civilization itself, with molecular estimates putting it at approximately 50,000 years old with an upper range of 150,000 years old. Many humans, both ancient and modern, were likely sent to their early graves by this disease.

Despite all the tools we have available to control these ancient diseases, typhoid and paratyphoid are still with us today, spreading through contaminated food and water and infecting about 30 million people a year, causing around 200,000 deaths. But thanks to the advent of modern medicine and antibiotics, these diseases no longer wipe out entire populations. As multi-drug resistance spreads rapidly, however, antibiotics become less and less effective in combating these diseases. Yet we have a weapon that the Aztecs and the Athenians never had: vaccines. The new typhoid conjugate vaccines in development could protect vulnerable populations from multi-drug resistant enteric fevers, but that depends on the world taking action. If the global community does not act swiftly to provide vulnerable populations with new typhoid conjugate vaccines and water and sanitation interventions, then typhoid, paratyphoid and related salmonelloses could become as deadly as they once were when they toppled empires.